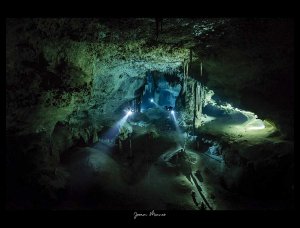

With the purpose of discovering and sharing the natural wonders of the peninsula of Yucatan through impressive images, the exhibition “Xíimbalil-Ja’, Kaxan ts’ono’oto’ob” (loosely translated from Mayan local dialect as “strolling through water, discovering the cenotes”) by photographer Joram Mennes, was inaugurated in Izamal, Yucatan.

The exposition opened on October 15th, 2020 on the fences of the very scenic convent of San Antonio de Padua, in the center of the quaint town. It then moved to Cholul – a Suburb of Merida, where the pictures were hung on the very fence protecting the local, center-town cenote. The concept of street-art made it readily available at no cost to the local inhabitants.

Photos courtesy of Maria José Jasso.

This exposition is meant to share the great treasures lying under the feet of the Yucatan Peninsula. Unfortunately, humans have a natural tendency to discard or ignore what they cannot see nor grasp, leading to the destruction of this unique treasure that are the cenotes and underground rivers. The purpose of the expo was to share and create consciousness. Not among cave divers, but among the communities who inhabit the area, who live beside the cenotes and caves, or above them. And, create a sense of global ownership of their heritage, and the inheritance of future generations.

For ancient Maya people, caves were an essential feature of their natural and cultural landscape. The caves and the cenotes interacted in a very active way with these societies. Beyond the utilitarian purposes of refuge and a water source, these formations represented a crucial element of the Mayan cosmovision and the way they perceived the universe. Among the ancient Maya, as well as in other prehispanic MesoAmerican cultures, the caves represented the entrance to the underworld.

This underworld was a place of death but also a place of rebirth and fertility. A dark and aquatic place where the gods of death inhabited, but also the place where the entire universe originated. These natural and symbolic features were part of the daily life of these ancient cultures. Many activities, ritual and non-ritual, were generated around the significance of the caves. This constant interaction resulted in a continuous cultural construction within these societies. Nowadays, these notions are still relevant.

Photo courtesy of Joram Mennes, Underwater Photographer.

The conception of the caves and cenotes among contemporary Mayans, even though modified by centuries of sociocultural reorganization, still carries a strong symbolism. They represent meaningful landmarks for the communities linked by generations with these terrains. The caves and cenotes still are active actors in the landscape that interact daily with the surrounding communities in many different ways. After thousands of years, they are still a fundamental component for the reproduction of culture within Maya, but also non-Maya societies.

Taken into account the aspect of the Mayan underworld, presents the dilemma of the Black Holes, not unlike the ones we have in outer space. It is thus very problematic, as the perception is more often than not of whirlpools that will absorb and suck anything in it – thus making it perfectly acceptable to throw any sort of garbage into “oblivion”. Before judging either the cultural background or the nefarious habits of waste disposal, it is worth the reminder that the state of Yucatan does not have within its program anything remotely close to environmental class or education, nor in primary or secondary school, for those who are fortunate to reach it. Those are left to citizen initiatives, such as Centinelas del Agua, Guardians of Cenotes, to name a few – in conjunction with private organizers who try to triangulate and synergize local authorities, Civic associations and the private sector.

Photo courtesy of Joram Mennes, Underwater Photographer.

With a basic minimum wage of 3060 mexican pesos per month (some 2140 after taxes and “mandatory contributions to the social apparatus”), respectively $150 USD and $105 USD, it is not an easy task to explain that conservation is an investment that will bear fruit, and not an additional cost to a derisory household budget. Yucatan does have the good fortune of having a low population density and spread-out villages, therefore lower impact than a megapolis. Most are developed settlements around a cenote. It makes it remarkably hard to reach and teach in a dynamic of racing against time, before the contamination (bacterial and physical) make irreversible damages.

As such, considering the historical and cultural background along with the economics, the idea of the street-expo was to present the titular picture as a black bottomless pit to create rapport with the stereotype of oblivion; only to break it through pictures showing the openings, tunnels, and magnificent rooms with a few divers only to provide scale.

The Title reinforces that concept, whether consciously or not, and we made a point-of-honor to have it in Mayan, along with a Mayan language video to facilitate diffusion amongst communities.

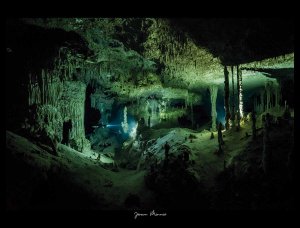

Photo courtesy of Joram Mennes, Underwater Photographer.

We are very pleased to share that the public response has been overwhelmingly positive, with a sense of ownership and community responsibility being outcried. We were thrilled by the demand to learn about practical solutions, and to develop synergies between art, culture, environment, and responsible social policies. We extended the Expo to Valladolid, another heritage town, with a series of presentations by different experts in their respective fields, in order to create bonds between the communities, share knowledge and ideas, and provide a sense of culture and beauty to finish a year that has seen everything but.

The colloquial conferences hosted in the magnificent Paparazzi Valladolid, included Water and Mayan Cosmovision, Exploring Cenotes, Truth and Myths on Solar Panels, Biofilters & Permaculture for Homes, Rooftop Gardening, and Organic Production, along with presentations from the Civil Association Centinelas del Agua. They share their work on educating youth about the cenotes and interconnection of the Peninsula’s water network, home improvements for a better world, and the Cenote Initiative by Fundacion Bepensa, AC.

The latter is of particular interest as they have been one of the most active patrons of the expo and the festival as a call for citizen participation. The Foundation, before the events of 2020, managed to clean 19 metric tons of rubbish from a little under 30 cenotes in Yucatan and had them evacuated by professionals. Against all odds, they resumed their cleaning activities when restrictions were eased – but cannot be the only ones to do so, nor expect any long term success if we, as global villagers, do not do our part as homeowners, visitors, business people, parents, and children.

Photos courtesy of Infolliteras.com

Conservation and protection of the Cenotes

Although we cannot deny there is a huge effort to be made from the local population to avoid contamination and protect the cenotes, it is worth mentioning there is an even greater effort to be made from foreigners. We, visitors, need to think several steps ahead as we have better knowledge and understanding of environmental matters and the means to contribute to their protection.

Our responsibility in trash management goes beyond depositing it in a wastebasket. We need to think of what happens next. If and when it will be collected? And where will it go then? Did we really need to produce that waste in the first place? How vital it is to bring a six pack of 150ml water bottles? Are we not the ones who bring waste to these remote places? Pampers and latex with our drysuits while locals wrap their toddlers in reusable fabric?

Think of the use of sunscreen, do we really need it when you visit a Cenote in the jungle or prepare for a dive in the ocean? Is mosquito spray really necessary before entering the water?

Is replacing a plastic straw with another disposable so-called “organic” or “biodegradable” straw worth it? Is the balance really positive for the environment? Think of the entire lifetime of the straw, the chain of production, the packaging, the transport, the recollection, the post-treatment? How necessary is the straw in the first place? Or taking a taxi to save us a 50 meter walk to the store?

As visitors, it is very important to act as an irreproachable role model, not to be judgmental, and to share our knowledge. As divers, we often trigger the curiosity of the locals or the swimmers and we should take a few minutes to share our experience and knowledge, and maybe show some underwater pictures when possible; it has proven to be very effective tools.

Photo courtesy of Joram Mennes, Underwater Photographer.

A Cave Diver and Explorer’s View

A presentation of the cenotes by a cave diver and explorer explained the slow process that leads to the cave formation and their unique characteristics.

Cave diver explorers with their desire of pushing the limits, have surveyed and mapped well over 1000km of underwater passages in the Peninsula. Some outstanding discoveries made along the way, such as human skeletons, archeological remains, and megafauna bones of extinct species were also mentioned to show their great contribution to science.

The cenotes also host and support the life of a particular ecosystem. Many endemic creatures inhabit the flooded cave passages, they have adapted to cave conditions and often lost their eyes and their pigmentation. Always of great interest for science, some of these species could become extinct before their discovery.

The importance of the cenotes as a water resource to the local communities and the local economy, was also reminded with the intention to emphasize the need to protect them. The equilibrium of the water is very fragile. Too many sad examples have proven that a rapid change or contamination can produce irreversible damage for the lifetime of our generation and most likely many more.

This presentation generated a great interest in the audience. It was the occasion for the local inhabitants to make peace with divers and cave explorers, often considered locally as looters or disrespectful to the local culture and patrimony. Sharing a passion for diving, cave diving, science, and exploration with the local population was a great experience and will hopefully lead to further collaborations.

Photo courtesy of Secretaria de la Cultura y las Artes, Gobierno de Yucatan.

The Exhibition

The exhibition “Xíimbalil-Ja’, Kaxan ts’ono’oto’ob”, has successfully brought to light the hidden secrets in the cenotes, and awakened the curiosity and interest of the local population. The pictures by Joram Mennes presented the aquifer well known around the world for its beauty. Featured in many international magazines, and heavily published in social media, the subterranean views are still poorly known locally, by the same people who live by the cenotes and depend on them.

The caves and cenotes are fragile elements of the natural landscape, they form part of a delicate and complex ecosystem, and their preservation is essential for the survival of it. The underground freshwater that flows within the cave systems in the Peninsula de Yucatán is fundamental for the subsistence of wildlife as well as for human society. By understanding the cultural and environmental significance of the caves, we all can collaborate in a better way in their conservation. At this moment, it is critical to have active cooperation between local communities, researchers, and explorers, and to recognize that learning from each other is the way to achieve a real impact.

The Festival Xíimbalil-Ja’!

By demand of the public and different partners, the organizers are very proud of the evolution of the expo, from artistic pictures with intent to the creation of a yearly festival of the same name, with plans for talks, more concrete workshops about water conversation as a system. Such as bio-filters and bio-digesters towards compost and waste separation as to produce soil for local communal and home gardening. Organic micro-agriculture, and cooking classes based on easy-to-grow readily available fresh produce, mainly under utilized.

Divers very often forget the utmost privilege of their passion and how little have the opportunity. The festival plans to have discovery workshops of freediving and diving for the youth. Unless we show the underworld that we adore to the local communities, it will be as futile and selfish to expect to bring any durable change.

Joram Mennes and the organizers wish to thank all the participants who have made tremendous efforts to make this happen, along with all of the sponsors for their encouragement and influx of energy. We would like to give a special thanks to Shearwater Research, our only international partner, for their support so far from their HQ.

Geraldine Solignac, Ph.D.

Cave Instructor and Explorer, Deep Dark Diving

Owner of VerbaMundi Translation Services (Eng/Fr/Esp)

Melissa Galvan, MA

Archaeology Ph.D. program, Tulane University, Louisiana

Avid and Passionate Speleologist

The post Xíimbalil-Ja’ Festival! appeared first on Shearwater Research.

Read MoreMonthly Blog Posts, Uncategorized, cavediving, diving, enviromental, environment, photography, scuba, scuba diving, tec dive, technical divingShearwater Research