TECHNIQUE

The Elephant in the Pool

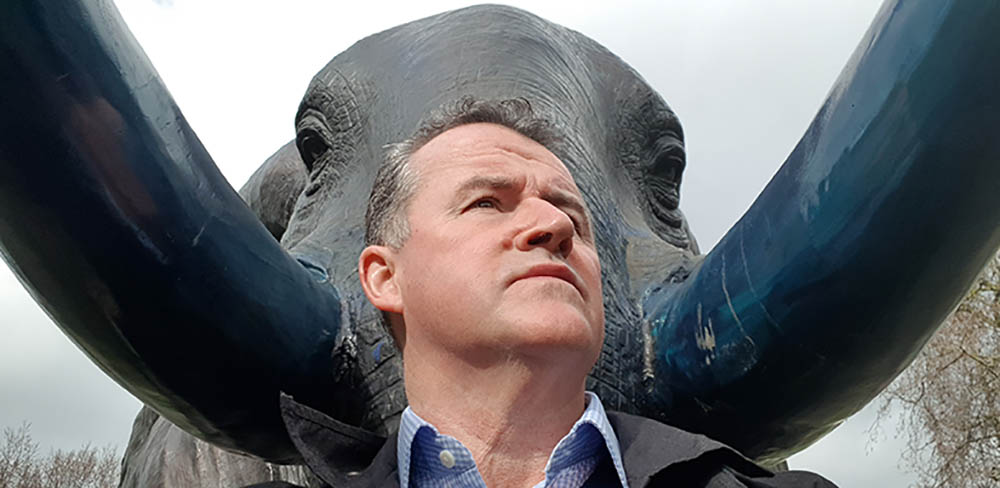

If buoyancy control is the key to good diving, why is it not a core component of commercial entry-level diver training? JOHN KEAN airs his views

The “elephant in the room” is the term used for an obvious flaw that’s blissfully ignored for long periods of time. Eventually the elephant makes its presence known, at the worst possible moment, at the greatest possible cost and causing maximum inconvenience to those on the wrong side of its trunk.

Two examples were Piper Alpha and Deepwater Horizon. The big grey things in the shape of overlooked safety procedures, complacency and commercial greed bit the offshore deepwater drilling industry in the rear harder than a Rottweiler with stainless-steel dentures.

Scuba beginner training doesn’t so much have an elephant in the room as a full-grown rogue mammoth in the swimming pool, swaying its huge tusks and trumpeting loud enough to crack the tiles the length of the pool.

What grand delusion is it trying to reveal?

In most sports, mastery is observable. Spectators at a tennis match can watch a ball being hit skilfully. A series of back- and forehands, serves or volleys culminate in a victory, or at least a visual display of prolonged competence.

The same goes for other sports, such as golf with its drives, chips and putts.

The evidence can be seen in how well the ball is struck, how straight and near to the hole it goes, and how few shots are taken to complete a round.

Over the past 20 years, parts of the new-diver training community have diluted and reframed what constitutes hard evidence of competence, distracting entrants from noticing its absence – the elephant in the pool. It’s inconceivable that vast sections of the industry are producing people who can’t dive properly – isn’t it?

Cert cards, wall certificates, graduation photographs, fridge-stickers, new equipment and logbook entries are all useful but they’re not direct evidence of a mastery of buoyancy control.

Sometimes we have the appearance of a competently completed beginner scuba course, but not always the hard visual evidence one might expect in other sports.

Appeared in DIVER June 2020

During an intensive entry-level scuba course we’re busy creatures. Look at all the necessary components: classroom or online theory absorption, extensive briefings and demos, kit set-up, donning and doffing, paperwork, admin and transport to and from locations.

There are the in-water training sessions in both confined and open water. Add the surface skills, quizzes, exams and multiple de-briefings and nearly a week has passed. At the end we’re safe and legal but… can we actually dive properly?

Among that list are some 25 inwater mandatory skills. They’re vital. Here are a few: descent and ascent procedures; out-of-air emergency protocols; clearing water from flooded masks; equipment removal and replacement; entries and exits; navigation skills; fin-pivoting; surface skills; finning techniques; cramp removal and assisting tired divers.

Lurking in there is the development of neutral buoyancy control. For me it’s the main event, not just a box on the instructor’s plastic skills slate to tick to fulfil legal and course standard requirements. It’s the most important skill to master because it defines what scuba is – diving!

Diving is controlled movement through water, and all the other skills, frills and social diversions in the world will never substitute for its absence or lack of development.

Neutral buoyancy control is used throughout all dives by all divers, yet its developmental associated skills on a beginner course are often the least practised. Why is that?

With about nine dives in the pool and open water adding up to nine hours under water, the grand total of mandatory neutral buoyancy skills with some agencies is not measured by hours or even barely minutes. It can be just – 90 seconds. Within that short time, the longest minimum requirement of a single buoyancy skill might be only 60 seconds.

A student can wing these 60sec “freeze frames”, much as a broken clock is right twice a day.

Some mandatory skills such as mask-clearing or cramp-removal might take only a few seconds to demonstrate, then copy.

Such skill-processing might tempt instructors to treat all the listed skills speedily, even though some require greater attention.

Worse still, nearly all the skills are done on a pool floor, rather than being repeated or additionally mastered in midwater, where a certified diver would typically be.

The way the world learns to… kneel?

Consider what goes into mastering neutral buoyancy control: BC operation, lung-volume control, correct weighting, trim achieved through sensible positioning of those weights and, finally, combining all these under a watchful eye through set skills and motion.

Consider what goes into mastering neutral buoyancy control: BC operation, lung-volume control, correct weighting, trim achieved through sensible positioning of those weights and, finally, combining all these under a watchful eye through set skills and motion.

This evolving sequence should take several minutes per student and be an ongoing process, but how many professionals give it the attention and respect it deserves?

The cynical might blame the training agencies’ limited mandatory inclusion of this vital skill, but is it really limited?

Here is a sentence accompanying a neutral buoyancy skill from the instructor manual of a leading training agency: “…inflate the BC to hover for at least one minute without kicking or sculling”.

Two words there are often overlooked by the impatient and agenda-driven resort instructor: “at least”.

During the swim-around part of the dive, it is encouraged that students be further exposed to isolated and deliberate development of neutral buoyancy-related skills over and over again.

So duration is left to chance, rather being a stated and required standard.

The “chancing” of diving’s most important skill is impossible to spot before booking a lesson, because a beginner doesn’t know it matters; many courses look the same in their marketing and course descriptions; and you might not know which instructor you’ll get and how seriously they take buoyancy control development until you complete the course.

Instructors in a hurry are prone to either rush this development or to believe that a few minutes is enough, despite visual evidence to the contrary. And how do they defend themselves? Easy.

They tell their less-than-neutrally buoyant ex-students that it’s… their fault!

“You passed, but now go away and work on your buoyancy control.” But, of course, that’s the instructor’s job from the outset.

Completing the mind-control exercise, additional courses are recommended to make up for the deficiency, offloading the consequences of failure onto other instructors.

These courses have names like “peak buoyancy control” and are often classed as “specialities”, courses intended to provide additional knowledge rather than to cover flawed entry-level training.

Not even the most short-sighted supermarket would offer “one for the price of two”.

Add-on extras in place of core areas of basic training appear not to exist in other fields of excellence. Graduating medical students are not told to “work on your transplants”.

Military passing-out parades rarely include soldiers who are rotten shots.

And I never heard of a fireman signing up for a peak-performance hosepipe course.

The elephant groans with incredulity when such instructors swap war stories about their students’ buoyancy-control woes, labelling them a “student from hell”, “bolter” or “human anvil”.

They blame drop-outs on “ear issues”, even though the real problem was caused by a lack of buoyancy control resulting in late equalising and damage to the middle ear.

With an unholy reverence for the authorities who sanctioned their own professional activities, few instructors will figure out that their basic training is the beginning, not the end.

Leading sports instructors study feedback and with a little reverse-engineering make the required adjustments to the learning process to achieve success. Following a script is useless if they don’t occasionally “look out the window”.

Technical-diving instructors frequently spot the elephant in the pool, because students arriving on their tech courses with sub-standard buoyancy-control development are either turned away, learn quickly or don’t get certified at all.

In the tech-instructor’s environment, good buoyancy control is not treated as just a “nice idea” but as a life-saver. An uncontrolled ascent from depth or the omission of multiple decompression stops with a body full of inert gas is game over, and it’s difficult to complete a peak buoyancy course when in a wheelchair or a coffin.

One would think that the knowledge-bank and vast experience of the tech instructor would be welcomed, but many resort recreational dive operations banish their “antics” from sight for fear of scaring their all-inclusive customers:

“He’s on the dark side.”

One sees the light when tech-diving because the increased risk that comes with greater depth and time is matched with knowledge, skills and discipline and neutral buoyancy mastery is at its core. That knowledge is easily transferable to recreational diving.

For example, recreational diving’s “Win it in a Minute” for neutral-buoyancy hovering has an equivalent in the first technical-diving course of

a mandatory 20-minute simulated decompression stop to within a metre of deviancy.

The recreational-diving industry has a small portfolio of tools and diversionary props to both accommodate and mitigate the effects of sub-standard divers.

Rarely do these include any form of improvement, and are more akin to railway buffers or motorway hard shoulders.

A private guide often becomes a private aquatic bouncer, keeping the “offender” arm’s reach away in non-challenging environments and at a safe distance from coral.

Further mitigation practices include the diver being relegated to “local sites” instead of the premier league iconic ones where the less-skilled would inflict more damage.

Fifteen-litre tanks are frequently requested or even “prescribed” in resorts because the guest is “bad on air and needs a bigger tank”.

Learner car-drivers who are bad on driving aren’t issued with an air-bag or sin-binned to a disused car park… they are taught to drive properly and pass a test under the evaluation of an external examiner.

Some experienced divers feel resigned to a life of short dives and a short leash, erroneously believing they are not among the chosen ones.

With the acquisition of some dive-centres by large travel and resort operators, the focus has been on volume rather than enhancing what is essentially a specialised sport.

Plane-seats, hotel rooms, beachside animations and excursions have been the mainstay of these corporate giants, and attempts at forcing the beginner dive-training industry into an image of its larger self hasn’t worked.

The “intro” dive, while satisfying the operators’ volume quotas, further removes the acquisition of skill, leaving just a momentary glimpse of life under water while securely attached to an instructor.

Because of the social, travel and community nature of scuba-diving it is also full of frills, attractions and diversions from achieving what really matters… the true mastery of neutral buoyancy control.

In many quarters the industry has sacrificed independence to unity, value to cost, quality to speed and professionalism to package.

The image they see around them is the product of ideals that have demanded more sacrifices at each successive disaster. High-quality resort diving is now a shadow of its former self.

The VIP luxury resort sector is also frequently oblivious to the elephant in the pool. While smart staff uniforms, good manners, polished service skills and reduced class sizes are marketed and welcomed in these gold-plated environments, neutral-buoyancy skill development can still be subjected to the Sixty Second Challenge.

I was once asked to supply a luxury resort’s dive-centre with an 18-litre scuba tank because its heavy-breathing billionaire diving guest was a demanding and valued customer.

I explained that its bulkiness was likely to cause yet more excessive air consumption. It’s a bit like running out of oil and using a longer dipstick.

The last time I saw any of these monsters, they were strapped to the back of world-record-breaking deep divers. “How about you teach him to dive properly?”

“We’re a 5* resort and we always give the guests what they ask for.”

The tail wagged the dog; two industries under one roof; room service competing with specialised instructional sports advice – a grey area?

It’s big and grey all right!

Visiting divers, in these circumstances, experience but a snapshot of what’s possible on their one-week diving holidays.

Visiting divers, in these circumstances, experience but a snapshot of what’s possible on their one-week diving holidays.

They might experiment on-the-fly with weighting, trim and position, only to crack it on the final day before flying home.

This is in blatant contrast to their guides, who flawlessly glide and hover motionless throughout the dive before surfacing with near-half-full tanks.

Are they gifted? Do they walk with the gods? Can they impart just a little of their heavenly knowledge during those multi-hour surface intervals?

The industry is still largely responsible for not only turning out thousands of divers who can’t dive properly but sustaining their continued lack of quality with props, diversions, illusions and little willingness to intervene and improve the status quo. So who is to blame?

No one and… everyone.

The offender is a mindset, a viral belief even, not an individual or entity that might accept or reject that mindset. If time and direct input is devoted to the problem, the results will show.

The solution requires nothing new. No gizmos, gadgets or “special training”. The professionals, agencies, dive-centres and equipment already exist and are well structured to provide the solution. All they have to do is… their job.

Unearned certification represents abdication of the responsibility that is the professional core of nearly any other field of education and training.

The alignment of agencies that don’t put neutral buoyancy development at the forefront, instructors who simply follow the printed word and decades of unsuspecting customers has created the perfect storm of cognitive dissonance, grand-scale Stockholm syndrome and perhaps the longest example of psychologist Solomon Asch’s Conformity experiment ever.

The result is a tightly woven tapestry of monumental illusion with few noticing that the aquatic Emperor really has no clothes. Scuba’s equivalent of “The Big Short”? It’s taken a very big shortie to keep this elephant insulated for so long.

Despite attempts to shoehorn dive training into the same buying process as Amazon orders, an entry-level scuba course that you can now “add to basket” is a service, not a product.

It might have an identical name and technical script to that offered elsewhere but its method of delivery and execution can be worlds apart.

If the existing gatekeepers have failed, the job falls to those who have already seen the elephant, whether they’re agencies, dive-centres or individual professionals. But is it all worth it?

In my long experience, here’s what happens when divers develop great buoyancy control:

• They feel good. Great diving experiences are not just about seeing, they’re about being.

• Their sense of safety and control is elevated; their air consumption drops.

• They dive more often, spend more, are easier to manage and less stressed.They tell others.

• You can take them to more interesting and exciting dive-sites. The underwater environment improves.

• They recognise value against cost. They’ll support your business.

Those outside the industry need to be presented with the information that lets them know they have a choice, what that choice is and who can deliver it. It’s not difficult and I believe all divers are entitled to it.

The elephant never forgets but after 20 frustrating years it’s getting rather impatient.

I think it’s time to drain the pool.

The post The Elephant in the Pool appeared first on Divernet.

Read More Dive Training, Technique Divernet