Your tanks are filled. Your regulators were just serviced. You head out on a boat or pull up to your favorite shore-diving spot only to discover there has been a major ecological disaster. An oil spill, massive red tide or other harmful algal bloom.

What have you lost? What has your community lost? It may be easy to see the dead fish on the beach but what is the true environmental and economic impact of this disaster? Those are questions that Reef Monitoring seeks to answer.

In 2005, I was a student at the University of South Florida finishing up a degree in Environmental Science. In order to graduate I needed a project to complete for my program. Having been certified in SCUBA since 2000, I was diving often and knew that I wanted to focus my attention in the water. Anyone that was diving on the Gulf Coast of Florida, specifically in the Tampa Bay area in 2005 may remember we had an unusual red tide event that year. The fish kills were quite prolific with thousands of carcasses lining our award-winning beaches. This was not a just a normal red tide event however. We also had an unusual thermocline that persisted throughout the summer and into the fall. Our normal summer hot water was sitting on top of a dense layer of very cold water on the bottom. What that did was compound the red tide effects. Some of the dead, rotting fish that did not wash up on shore sank and were trapped beneath the thermocline. This created a low oxygen situation in the water along the natural and artificial reefs on which we depend in the Gulf of Mexico. The reefs were devastated. In addition to the fish that were killed or driven away from the reefs, all the invertebrates were also killed. Starfish, sea urchins and soft corals were all wiped out. The hard corals were bleached out and dead. Diving during this event was eerie. All the normal “snap-crackle-pop” that you hear while diving was gone. The water was dark and quiet and it was freaky.

Photos provided by Reef Monitoring, Inc.

The project I decided to do for my degree was to study the recovery of two particular reefs after this devastating kill. The reefs chosen were within 5 miles of Clearwater Beach, FL. One was a man-made artificial reef consisting mostly of concrete culverts and the other a nearby natural reef which was a limestone ledge. I was interested not only in seeing how these reefs would recover but also comparing the artificial reef to the natural reef and to see if there were noticeable differences between them. Can man build a better reef than nature that would bring back fish and thrive faster?

Photos provided by Reef Monitoring, Inc.

Photos provided by Reef Monitoring, Inc.

The method I chose was to conduct underwater visual surveys by Roving Diver transect using a reel with 50 meters of line on it. I would swim around the reef randomly while laying out the line and counting a specific set of species that are within 1 meter on either side of the line. 50 meters of line and 2 meters wide gives you a total sample area of 100 square meters. This is a long-proven scientific method to be effective in establishing resident reef populations.

Photos provided by Reef Monitoring, Inc.

While performing the count, I keep track of the species on an underwater clip board with a data sheet on waterproof paper. The data sheet tracks the site-specific data like the location of the reef, the date, tide state (rising, falling or slack), the water temperature, visibility that day and other empirical data.

The first part of the data sheet tracks fish species. Species that have value to the public both environmentally and economically. Popular fish species like groupers, snappers and hogfish that we see on our plates at restaurants. These fish play a crucial part in Florida’s economy. Florida is known for its grouper so it was a particularly important family of fish to watch! The fish are counted while swimming “out” and laying out the line since they can spook by your presence and swim off.

Photos provided by Reef Monitoring, Inc.

While reeling the line back in, I also looked at important invertebrate species like starfish, sea urchins and soft corals like the purple sea whip. The purple sea whip is a fragile soft coral that will be killed easily if the water quality deteriorates. This was an important species not only for this project but going forward. In 2010 after the Deepwater Horizon/BP oil spill disaster, we were all closely monitoring (and still are) for hydrocarbons in the water. The purple sea whip became our “Canary in the Mine” that can alert us to issues with water quality that we may not be able to see otherwise.

Photos provided by Reef Monitoring, Inc.

In early 2010, Reef Monitoring, Inc was officially incorporated as a 501(c)3 research organization. I had still been performing the underwater counts and myself along with Dr. Heyward Mathews, Dr. Monica Lara and some other local scientists decided to expand our outreach. We realized that we could teach everyday sport divers how to conduct these underwater fish counts. The more data we could get, the more we could establish a baseline set of data on our fish populations. This could be invaluable information in case we ever got another really bad red tide event. Well, soon after we did not get a red tide event. What we got was a disastrous oil spill in the northern Gulf of Mexico when the Deepwater Horizon oil rig tragically caught fire. We realized the need more than ever for this baseline data.

We teamed up with local dive shops and clubs to teach as many divers as possible how to conduct the surveys so they could go out on their own and perform them and give the data back to us. Reef Monitoring continues this program today.

Photos provided by Reef Monitoring, Inc.

It was also important for us not only to track the species that were on the reefs already but also the species that were newly settling onto the reef. When fish and invertebrates are hatched, they float around in the water as larvae until they settle down onto a reef. This is new recruitment to a reef and can be a critical gauge to how healthy a reef is. Is the reef just attracting adult fish from other areas or are new organisms establishing themselves on the reef?

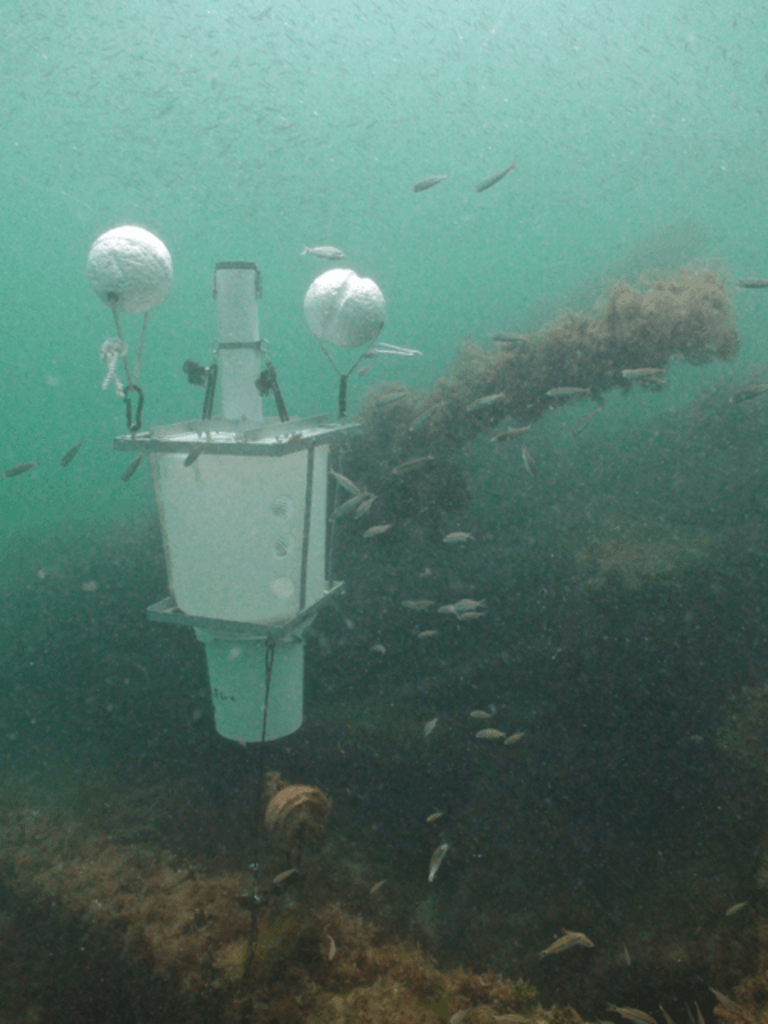

To determine this we use a device called a Light Trap developed by one of our board members, Dr. David Jones.

Photos provided by Reef Monitoring, Inc.

This device is deployed onto the reef during a dark moon phase so there is no other light in the water. Larval organisms are attracted the light and swim into it and are trapped. We retrieve the traps at dawn and study the contents. This allows us to determine what (if any) new larval fish and other organisms are settling onto the reef.

See our Light Traps in action and Dr. Lara gives a more thorough explanation!

So you’re probably wondering which reef recovered better, yes? The easy answer is they both recovered, but differently. Fish populations immediately came back to both reefs in a short period of time. The soft corals grew back. The reefs are healthy again. There were some interesting observations to note. We did not see a starfish or sea urchin on the artificial reef for over a year after the kill. On the natural reef, the limestone surfaces that previously held mostly soft corals and sponges were now covered in colonial tunicates. The tunicates were not particularly observed in large quantities before the kill but were noticeably outcompeting the sponges and soft corals after the kill for bottom substrate on which to attach.

Photos provided by Reef Monitoring, Inc.

Today, Reef Monitoring continues to have the visual surveys and Light Trap studies as the core to our research. Reef Monitoring is a 501(c)3 non-profit research foundation dedicated to the research and education of Florida’s marine ecosystems. Reef Monitoring is not government funded and no member has ever taken a salary. We are entirely funded by the community and local businesses. Reef Monitoring works closely with St. Petersburg College in Clearwater and has several professors on the board. In addition to underwater research, Reef Monitoring holds free symposiums to educate the public and allow our students and scientists to interact directly with the community to display our findings. Reef Monitoring also holds Reef Clean-Up events and together with our friends and colleagues have removed thousands of pounds of crab trap rope, fishing line and other garbage from our reefs. We have partnered with outstanding organizations like the Clearwater Marine Aquarium and the Tampa Bay Lightning to continue our research.

Photos provided by Reef Monitoring, Inc.

Our reefs are healthy as ever and there is some fantastic diving to be done in the Tampa Bay area of the Gulf of Mexico! Come visit us and do some diving. In the meantime we’ll keep an eye on the reefs for you.

The post What is Reef Monitoring? What can we learn from the data? appeared first on Shearwater Research.

Read MoreMonthly Blog Posts, enviromental, reef monitoring, reef-health, reef-world, scuba diving, ShearwaterShearwater Research